The Wall Street Journal visited our program in Mount Elgon, Uganda, to understand how cash transfers can help people in poverty who are most impacted by the effects of climate change, despite doing the least to cause it. They highlight a community that has suffered from frequent landslides due to extreme changes in rainfall, and which is now being relocated to areas less prone to landslides. This is the largest climate-linked resettlement program in sub-Saharan Africa.

By Nicholas Bariyo

Photographs by Badru Katumba for The Wall Street Journal

December 6, 2023

BUDUDA, Uganda—On a steep slope dense with coffee and banana plants, farmer Irene Muyama starts each day by carefully checking a 5-inch-wide crack that recently appeared on a path her children take on their way to school. She has packed the family’s meager belongings into a pile of handwoven baskets, preparing to move to a new, safer home.

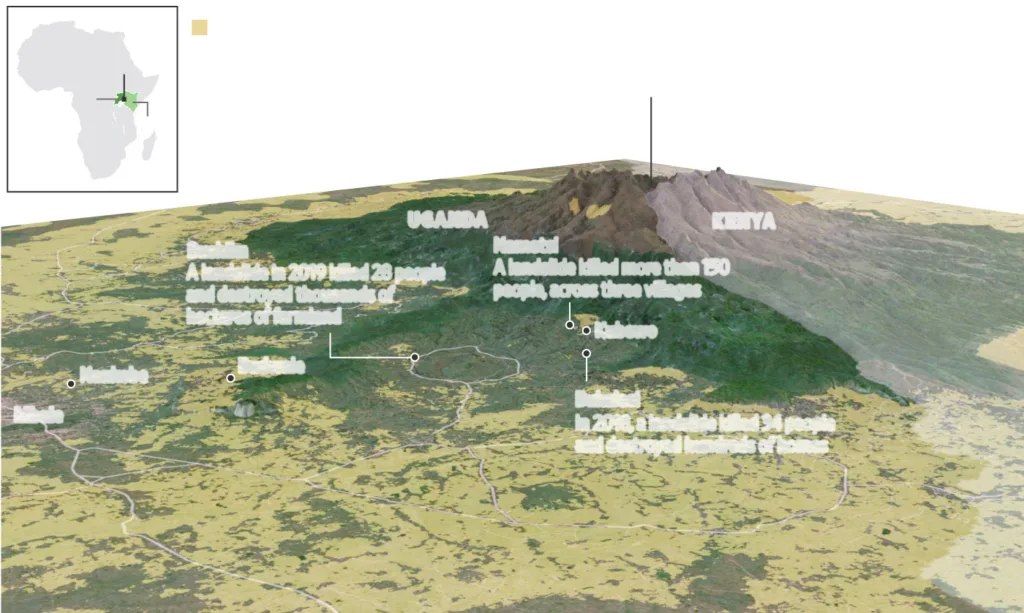

The fertile highlands of Mount Elgon, an extinct volcano straddling Uganda’s border with Kenya, have become too dangerous for people to live and farm on, the Ugandan government says. The mountain has long produced some of the world’s finest Arabica beans for U.S. brands like Starbucks and Blue Bottle Coffee. But a series of deadly landslides that climate scientists say were caused by extreme changes in local rainfall patterns have thrust this mountain—and the people who live here—to the center of one of the most divisive battles in international climate negotiations.

Since 2010, landslides triggered by destructive and increasingly erratic rains have killed more than 1,000 people on Mount Elgon, according to data from Uganda’s Disaster Ministry. In the preceding two decades, 59 residents died in landslides on Mount Elgon, the ministry says. Among those killed in recent years were three of Muyama’s relatives, including an aunt who worked as a teacher and was swept away in 2019 along with her classroom and dozens of her students.

Last month, the government started relocating the first of what it says will be a total of 100,000 residents—about one-tenth of the population of the four districts that cover the Ugandan side of the mountain—to areas less prone to landslides.

The Mount Elgon resettlement is the largest climate-linked relocation program in sub-Saharan Africa and one of the biggest globally. The World Bank says that 216 million people worldwide, most of them in developing countries, will have to move by 2050 as climate change makes their current homes too wet, too dry or otherwise no longer safe for human habitation.

How to pay for new shelter for people being displaced in countries that historically have contributed little to the global greenhouse gas emissions that drive climate change is one of the central points of discussion at the COP28 Climate Conference in Dubai.

Developing countries, including Uganda, have asked rich nations to double their annual financing of so-called climate-adaptation projects by 2025 from just $20 billion in 2019. Thereafter, these countries say they will need tens of billions of dollars more every year to provide new homes for the displaced and build protective infrastructure like dams, irrigation systems or fortified roads that will allow people to stay where they are.

“Poor communities in Uganda are already facing the brunt of climate change,” Beatrice Atim Anywar, Uganda’s environment minister, said in an interview. “Yet as a country we have limited resources to help them cope.”

Last week, international climate negotiators said rich countries would start contributing to a new fund meant to help communities like those around Mount Elgon, that are forced to move or suffer other severe damage because of climate change.

Anywar says her government has raised less than half of the $32 million it needs for resettling the Mount Elgon residents. The first round of relocations is financed in part through a $7.2 million grant from U.S. charity GiveDirectly, which has provided one-off payment of around $1,800 to 4,000 families to help lay the foundation for their new lives.

One of them is Muyama, the farmer worried about an expanding crack in the soil near her house. She is using the money to build a three-bedroom house for herself and her seven children on a small plot of land about 10 miles from her current home.

“I will leave everything behind,” Muyama said recently, while sorting through a basket of freshly harvested red coffee beans. “Coffee doesn’t grow well where I am going. But I have no choice. I will not risk my life any longer.”

During harvest season, Muyama earns about $150 a month selling Arabica beans to local traders, who in turn sell it to agents representing global coffee giants such as Starbucks and trading houses like Volcafe and Sucafina, both based in Switzerland. She hopes to cover part of the lost income from growing green beans, which are a staple in Uganda but have much lower margins than coffee.

“I don’t know how I will look after my children, without income from my coffee garden,” she said.

Starbucks declined to comment. Representatives for Volcafe, Sucafina and California-based Blue Bottle Coffee, which is majority-owned by Nestlé, didn’t respond to requests for comment.

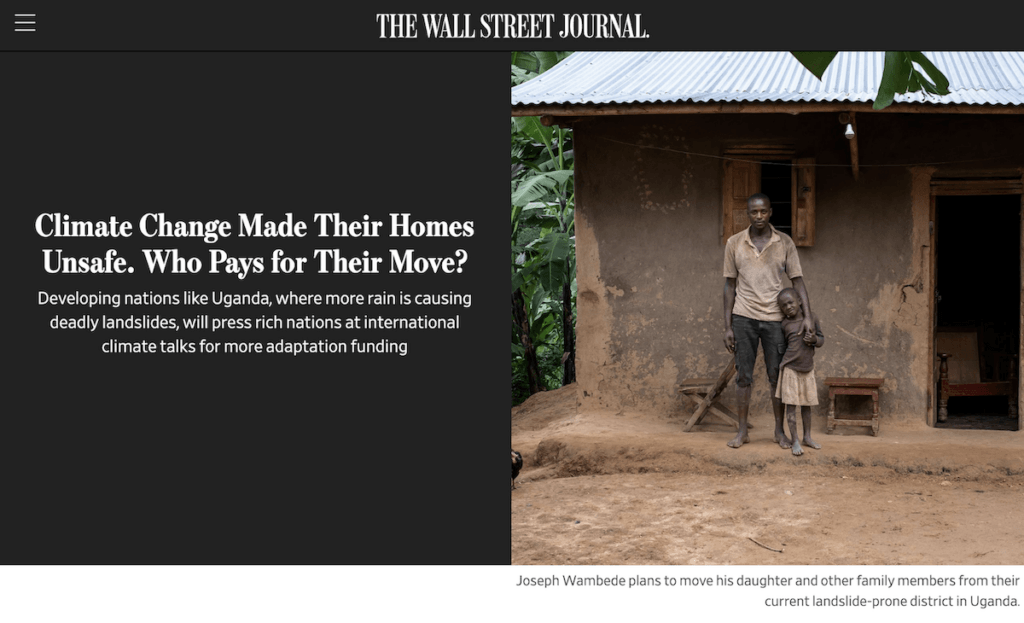

One of Muyama’s neighbors, Joseph Wambede, spent part of his donation from GiveDirectly to buy a motorcycle, which he plans to use to transport customers and goods and help him earn a living once his family moves to their new house. The 28-year-old father of four says the plot of land provided by the government is only about a half acre—around one-fourth the size of his current fields on Mount Elgon.

“We are on tenterhooks every time the rainy season begins,” he said in the yard of his iron-roofed mud-and-wattle house. “My plan is to be out here by January, before the next rainy season.”

Michael Singer, a professor at the School of Earth and Environmental Sciences at Cardiff University in the U.K., is part of a team of international scientists who recently published a study on the climate around Mount Elgon.

They found that the Mount Elgon region has experienced some of the most dramatic changes in annual rainfall patterns documented globally, turning an area that previously was mostly prone to droughts into one that gets increasingly more rain.

“The recent wet periods around Mount Elgon in the past three years are unprecedented,” Singer said. “We have learned from our study that climate change is causing huge problems to the local population.”

Between 2003 and 2023, Mount Elgon experienced four times as many wet months as in the previous 20 years, while the number of dry months fell by about 50%, the study found.

Over the past four years, staff from GiveDirectly have checked the Ugandan side of the mountain for cracks and other signs of potential danger to help them identify families facing the biggest risks. Most of the Kenyan side of Mount Elgon forms part of a national park with few permanent residents.

“Our teams are identifying more people in urgent need of help around Mount Elgon, but we are facing funding shortages,” said Ivan Ntwali, the Ugandan country director for GiveDirectly. “Donors are not prioritizing funding for climatic adaptation.”