Recipients

How we collect recipient stories for GDLive

Giving money directly to people in poverty recognizes both the dignity of the individual and the diverse needs within a single community. Our stories try to represent these same values. In that spirit, rather than sharing a curated set of stories or trying to summarize people’s experiences, we try to give the audience a fuller, unfiltered picture through our GDLive product.

We follow up with people after they’ve received their cash transfers

We check in with every person at each stage of the cash transfer process to answer any questions they have, and ask questions to see how things are going:

Enrollment: When a village is being enrolled to receive cash, GiveDirectly field officers travel to enroll recipients at their homes and give them a phone. Recipients are asked a few questions, and their answers are translated from the local language into English. These answers entered into a form and uploaded into a database.

Check-in: After each payment, we call recipients to hear more about how things are going. This is to ensure that they haven’t faced any issues or faced harm while accessing their funds (read more about how we prevent and report on risks). This feedback is entered into the database as well.

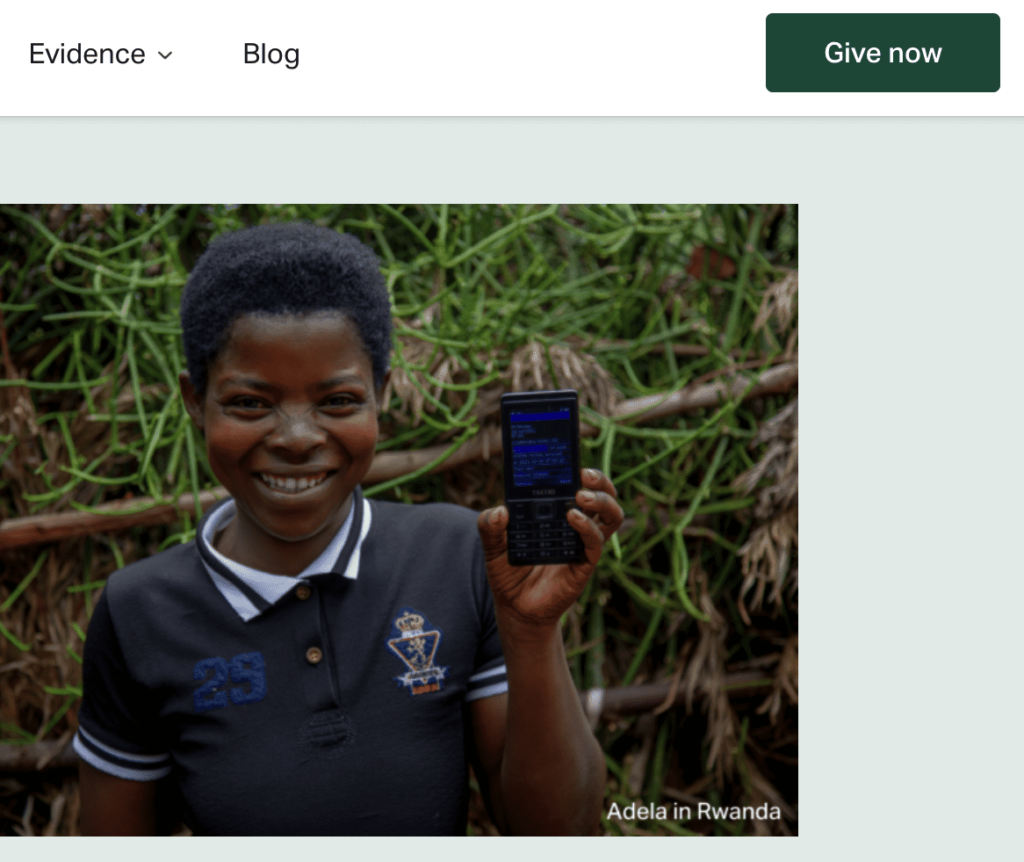

Story published: The photos and quotes are then published in real time on the GDLive website. These recipient updates are shared to help give the GiveDirectly community a better idea of how their donations are helping to transform the lives of families in poverty.

We aim to document people in poverty ethically and honestly

Extreme poverty is defined by economists but lived by real people. Sharing their stories amplifies the voice of communities rarely listened to and is vital to helping donors understand the realities they face. You can read “17.4M Yemenis are food insecure,” but research shows you’re more likely to remember and respond to Omar’s story of fleeing violence and struggling to feed his family. Stories humanize the problem and, yes, raise more money, but they do come with risks.

First, we get consent and make sure it’s as informed as possible

People in poverty are often documented without their consent, in what photojournalist Chester Higgins calls “theft pictures.” For one example, listen to the story of how this famous magazine cover of 12-year-old Afghan refugee Sharbat Gula was captured.

GiveDirectly only documents recipients with their formal consent, or in the case of minors, both their and their parents’ consent. They opt to sign a plain-language form translated into local languages, which they are given to keep. If they are unable to read the form, our staff reads it aloud. Our form aims to explain two things to recipients:

- We emphasize that receiving aid is not contingent on sharing their story. This is vital because communities in poverty are used to aid groups arriving with a list of conditions––farm with this tool, read your kids this book, pose for this photo––in order to receive urgently needed help, habituating them to say ‘yes.’ GiveDirectly tracks if recipients know they can decline without consequences through focus groups and overall rejection rates (44% last year over all our programs).

- We explain that their story may be shared publicly across the internet. While some recipients have high media literacy (e.g., starting a LinkedIn page), most in rural areas do not––in many villages, we’re issuing over 75% of residents their first mobile phone. To bridge this gap, we show them examples of other stories on the internet and explain many people around the world may see their story.

We identify who they are and where they live

Using identifiable people as unnamed stock images unnecessarily flattens the experience of poverty. Design has limitations––we cannot capture someone’s full interiority in display ads––but at a minimum, GiveDirectly includes the first name and country of individuals we photograph.

This is an admittedly low bar, but one that is rarely met by others. Open up the website of another charity and ask how many of their portraits display the subject’s name and nationality? These often Black and Brown subjects are paired with headlines about poverty, stripped of any context as to who they are, where they live, or why they specifically were featured. Getting this right isn’t easy, but we encourage other charities to adopt the first-name-and-country standard.

We’ve made mistakes in our storytelling in the past

In our decade of work, our storytelling style has progressed. It’s useful to look back on some ways we erred, as it informs our thinking going forward.

- We underinvested in sharing recipient stories early on. As a research-driven organization, we thought statistically significant improvements to food insecurity indices told the story well enough (0.01 p-value deviation! Cue the Sarah McLachlan). Many of our wonkiest donors agreed, so we didn’t prioritize documenting the human side in the first few years.

- We shied away from showing the realities of extreme poverty. Turned off by overwrought imagery we saw from others, some of our storytelling skipped over the harsh “before” picture to focus on the more empowering “after” cash transfers. We assumed our audience understood the general severity of extreme poverty, so we focused on the good news. This omission sold short the challenges people in poverty are facing and the full impact of your donations.

- We used inscrutable consent forms. For several years, we used a boilerplate image release form written in such dense legalese that our own staff could barely understand it. While some binding contractual language is required, this form certainly did not receive informed consent (read our new one).

- We did not identify people’s names or countries. Until 2021, we often used images of recipients on our website and social media pages without identifying their first name or nationality––we simply did not consider the alternative. While we’ve since switched these out in our own materials, some well-meaning supporters still circulate these older images on their fundraisers and pages.

As we continue to improve our practices, we’d love to hear your thoughts. Send us feedback at info@givedirectly.org.